In business, finding a polite way to break off a conversation is as tricky as it is critical. Time is money, so you don't want to chit-chat with a client or a colleague longer than necessary, but respect buys time, so you don't want to betray any annoyance or impatience. Short of the classic hidden button beneath the desktop that rescues us with a well-timed "call," or perhaps a modern smartphone app equivalent, we perform our best conversational gymnastics and hope society judges us kindly.

The clumsy among us can turn to the behavioral evidence on ending a conversation that's been compiled over the years. Though humanity has been finding delicate ways to part ways since the dawn of spoken language—I'd love to grunt more, said the caveman, but I have a rather fast predator to avoid—scientific study of cutting off a discussion didn't occur until the 1970s. The research is a bit scattered and intuitive, but it does offer a few guidelines on general norms for ending a chat, be it pleasant, intolerable, or otherwise.

One of the first impressive empirical studies was a Purdue University research project from 1973. Researchers paired up 80 test participants for a semi-structured-interview, with one party instructed to break off the discussion as quickly as possible after obtaining certain information from the conversation partner. The semi-formal, goal-oriented task served as a fine proxy for many business situations (which may help explain why the research was funded, oddly enough, by U.S. Steel).

After analyzing the final 45 seconds of the interactions, the researchers coded and tallied up the most frequent "leave-taking" behaviors. These included "reinforcement" (short, tacit agreements, such as yeah and uh-huh), "buffing" (brief transition terms, such as well and uh), and "appreciation" (an encouraging declaration along the lines of I've really enjoyed talking with you). These verbal maneuvers occurred with enough consistency for the researchers to diagram a typical pattern of closure:

The frequency of the reinforcement and buffing combination suggested to the researchers that people like to give a sort of courtesy warning before wrapping things up. Merely saying Yeah, well may give the other party a chance to finish up a thought and consent to the break-up without looking foolish (like the way we say All right! in a higher pitch to announce that a phone call should end). This tendency may reflect the fact that ending a conversation is somewhat negative by nature, so offering subtle signs of support and chat-end coordination can preempt any ill feelings.

"Perhaps because we feel that the termination of an interaction may be perceived as a threat to terminate the relationship," the researchers conclude, "we humans go through a veritable song-and-dance when taking leave of our fellows."

In the years to follow, social scientists expanded these findings to paint a fuller picture of social departures. University of Washington psychologists observed the final 15 seconds of conversations by 185 test participants and found that people tended to shift their posture in the moments before ending a chat. During the heart of the talk, 121 of the participants stood with equal weight on both legs; toward its conclusion, 107 put more weight on one leg—as if to signal a "readiness-to-depart [that] prepares the members of the interaction for a social transition."

Meanwhile, psychologists Stuart Albert of the University of Pennsylvania and Suzanne Kessler of SUNY-Purchase settled on a common formula for ending social encounters: Content Summary Statement, Justification, Positive Affect Statement, Continuity, and Well-Wishing. The translation, in everyday terms: "Well, we covered everything we needed to [Content Summary Statement], and I have another meeting [Justification]. I really enjoyed getting together [Positive Affect Statement]. Let's do it again next week [Continuity]. Take care [Well-Wishing]." And in scientific terms:

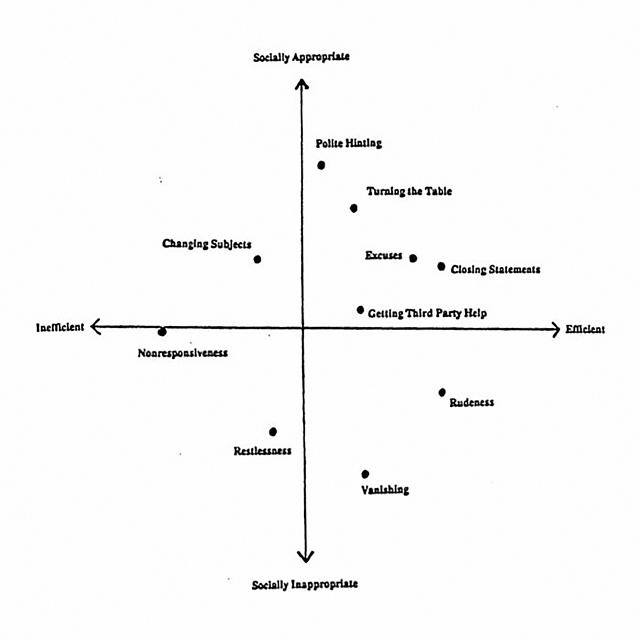

Early research tended to overlook the fact that not every conversation ends on mutual terms. Sometimes one party feels compelledto retreat before the other party might be ready. Such behavior was harder to emulate in a lab, but by asking people to recall instances of breaking away from a chat prematurely, researchers identified at least 10 clusters of "conversational retreat tactics" that most people employ. In a 1989 doctoral thesis, Josephine Bao-Sun Chen illustrated these tactics with a four-part plot of socially inappropriate-to-appropriate and efficient-to-inefficient.

Toward the socially inappropriate end of the spectrum is a rudeness strategy (e.g. cutting someone off mid-conversation), while a far more appropriate alternative is polite hinting (I wish I had more time…). Toward the inefficient end is a strategy like nonresponsiveness—acting disinterested, for instance, or giving quick, monosyllabic replies—that may or may not get the point across. Far more efficient approaches include excuses, for those who don't mind a little deception, and clear closing statements ("I have to go now"), for those who do.

The lessons of this line of evidence may be largely intuitive, but they remain valuable today. Just this September a report was released on the right ways to end business conversations at a professional conference, echoing many of the norms scientists have tracked over the years. There were certain techniques for ending a productive conversation that both parties knew had run its course (e.g. I'm glad we had the chance to talk), and others for ending a chat that was draining one party's time without offering any benefits (Why don't you give me a call next week?).

But perhaps the greatest lesson the literature has to offer is that none of us are quite as good at gauging when to end a conversation as we'd like to believe. In one study from years back, test participants reported that they had to retreat early from a conversation quite often, about 45% of the time. Yet they also reported that their conversation partners did not retreat often and that it was rare for these same partners to think a conversation had gone on too long—suggesting that we think other people are enjoying what we're saying perhaps more than they really do.

On that note, if you're still reading by now, I'm sure you have somewhere else to be …