You've probably heard the statistics on how under-represented women and minority leaders are in American business, but they bear repeating so get ready to hear them again. Women make up nearly half the U.S. labor force but account for less than 15% of executive officers, and only about 5% of Fortune 500 CEOs. At 12% of the labor force, meanwhile, African Americans make up a small fraction of managers, and only seven head Fortune 500 companies.

Of the many reasons for this leadership gap, a strong contributing factor may be the hidden gender and racial bias that occurs when people in charge delegate power. A trio of psychologists from Penn State University document this uncomfortable (and perhaps unconscious) tendency in a new study published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. The result, whether intended or not, is that the heirs to business leadership tend to look a lot like those who already have it.

"Biases used by those in power can therefore perpetuate and reinforce the status quo between dominant and subordinate groups," the researchers conclude.

The study team, led by Nathaniel Ratcliff, reached their findings through a clever laboratory game that simulated a leadership situation. In one experiment—the one focused on gender—Ratcliff and company told 96 test participants they were going to lead a small group in a virtual, computer-based capture-the-flag contest with a $25 prize for winners. As group leaders, these participants had to make the key strategic decisions about flag location, attack scheme, and defense placement.

Shortly before the contest began, the group leaders received messages from their team members. In fact, no team members existed, and these messages had been manipulated by the researchers to trigger gender-based responses. Some messages came from team members with obvious male names, like Matt or Eric; others came from members with clear female names, like Lauren or Nicole.

After test participants received the outcome of the capture-the-flag game—some won and some lost, with the results chosen randomly by the researchers—they were given several options with regard to their leadership in advance of a subsequent contest. They could keep full power over the team to themselves, or retain power but get feedback from team members. They could also delegate a co-leader to help with strategy, or even relinquish total control to someone else.

In general, Ratcliff and colleagues found that test participants who lost the first game, and thus had reason to question their leadership skills, delegated significantly more power to team members compared with those who won. More specifically, losing leaders were significantly more likely to relinquish power to a team member with a male name than a female name (below). The same did not hold true for winning leaders, who delegated less power overall, but did so indiscriminately.

Critically, about half of the test participants were women themselves. So it wasn't just that men tended not to give up power to women; women didn't give power to women, either. There's more: female test participants who lost the contest—again, calling into question their leadership ability—gave up significantly more power than losing men did, suggesting to the researchers that women may have "a lower threshold to relinquish their power to remove themselves from leadership."

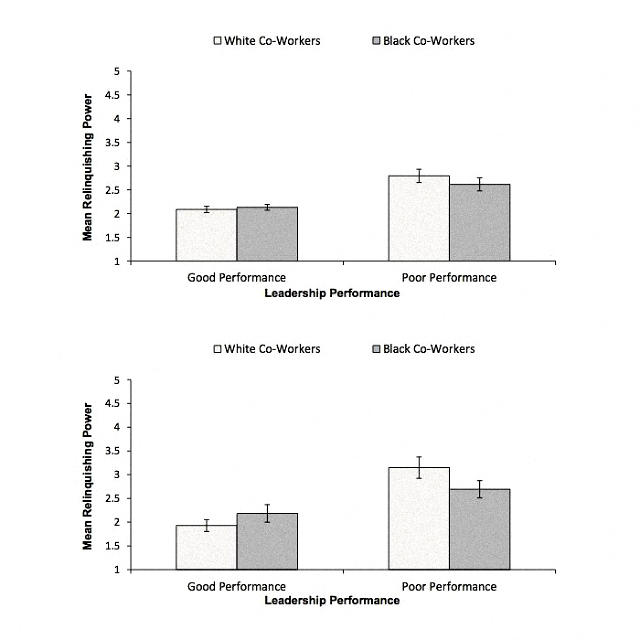

In a separate two-part experiment based on race, with names like Lamar or Tyronne serving as a proxy for black team members, Ratcliff et al. reached similar conclusions. Once again, test participants relinquished significantly more power following a loss indicative of poor leadership. And once again, among losing leaders, more power was delegated to teammates with white-sounding names than black-sounding ones (below).

The study, which calls itself the first to document group-based biases in power decisions, raises a number of questions for further investigation. Would leaders have shown the same tendencies if they knew more about team members than just their names—say, perhaps, their qualifications? And are underperforming leaders truly more race- and gender-biased than successful ones, or do they just seem that way because they're more inclined to delegate power, period?

On its own, though, the new evidence reveals yet another layer to workplace equality: even once women and minorities are hired and get promoted into a position near power, they may not truly be seen as leaders-in-waiting. Subtle and small as delegation bias may seem, write the researchers, its effects can "accumulate into striking differences" over time and across large populations. As striking as the leadership gap found in American business today.